My Journey: Breaking Production at a PSP Company

Joining the Company

My second job came right after leaving the startup I wrote about in my previous post. This time, I joined a Payment Service Provider ( PSP) company as a consultant. For context, a PSP is basically the middleman that handles online payments: when you buy something online, they’re the ones making sure your card works, your bank approves it, and the money gets to the right place.

During my first few weeks, I bounced around different teams doing small tasks here and there. Honestly, it felt like they had hired me without really knowing where to put me, which happens sometimes—they just want someone ready for when a need pops up. Eventually, I landed in my final team: Payment Core, the team responsible for handling payment requests from start to finish. When a merchant redirects a user to our payment page (or calls our API), we take over from there until the transaction is completed.

At that time, most of our clients were using payment by redirect, where users are sent straight to our hosted payment page. Our product let clients customize that page a bit—things like adding their logo, changing some text, or tweaking the layout. The page itself was pretty simple: a summary of what the user’s paying for, and input fields depending on the payment method (but honestly, 95% of the time it was just credit card fields).

And it’s actually this customization feature that’s at the heart of the incident I’m about to tell…

Joining the Team and Taking the Ticket

I joined the team and quickly noticed something odd—we were three junior backend devs, all consultants from different agencies, plus the tech lead. Honestly, it felt a bit strange to have an entire team made up of juniors and consultants who could leave anytime. It was a big shift from the startup environment, where we constantly took initiative and tried to improve things. Here, building even a small feature followed a strict process, and no one really questioned if there was a better way to do it.

Since they found out I’d done some frontend work while waiting to join the team, I suddenly became the “frontend expert.” You know how it is—if you show even a little skill in something, congrats, you’re now the expert. So naturally, they handed me a frontend ticket they’d been struggling with for six months, one that kept coming back with regressions or some edge case failing.

I’ll explain what the ticket was in the next section.

The Ticket

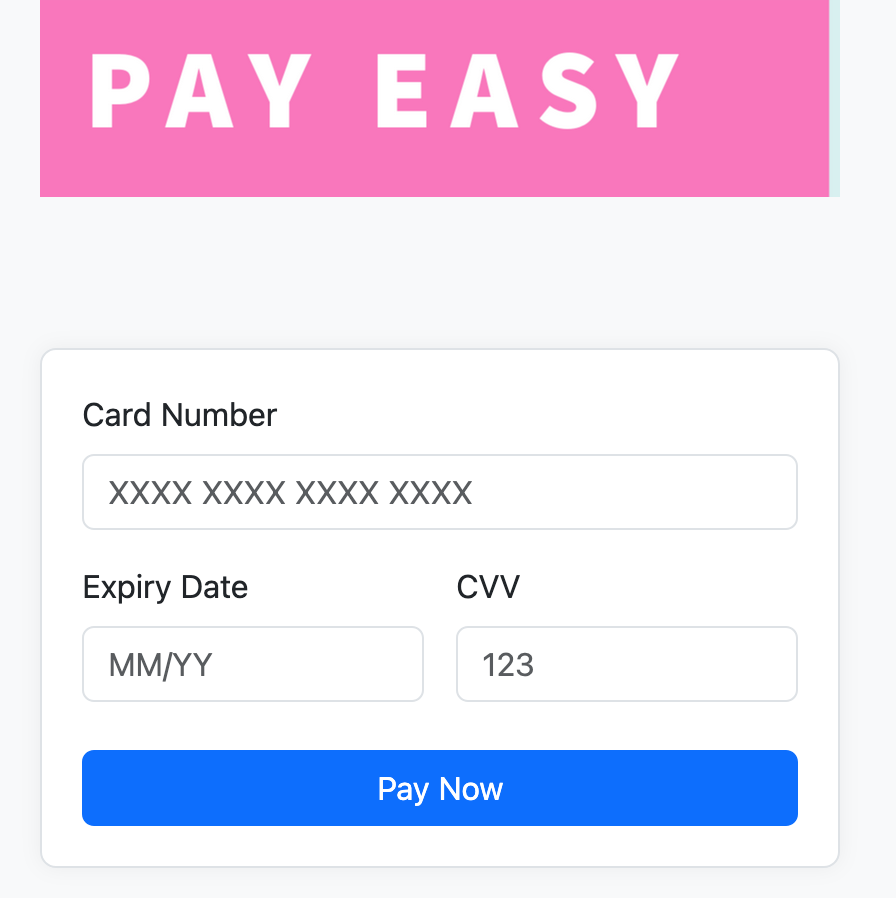

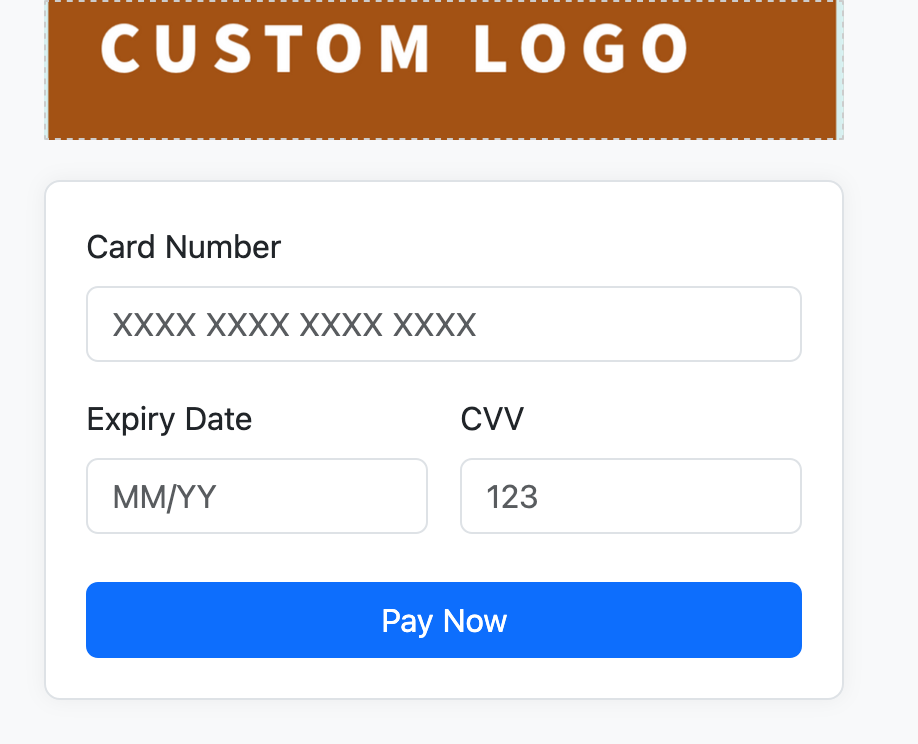

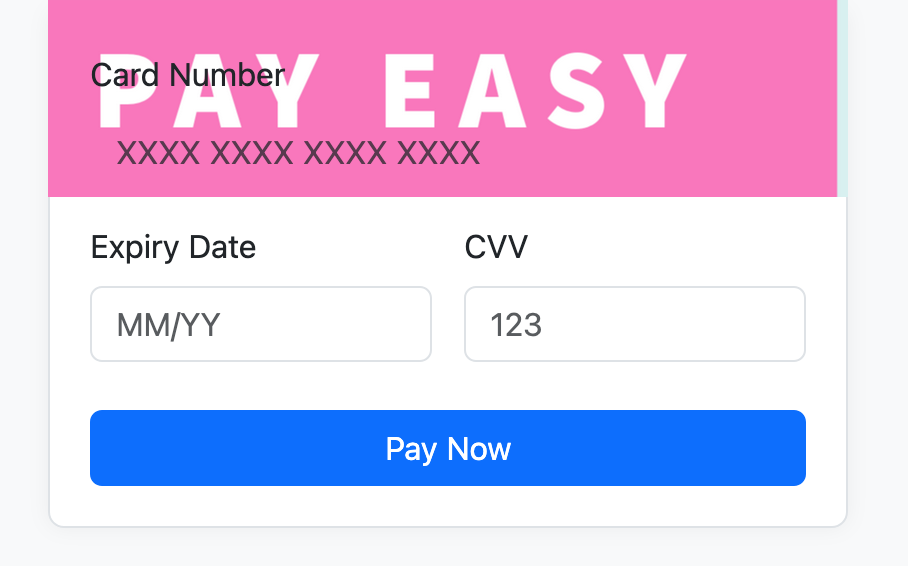

Our payment page was structured into two main blocks: on the left, we showed details about the payment (which isn’t relevant here), and on the right, we had a header block with the credit card fields below it. Clients could customize the header—by default, we showed our company logo, but they could remove it entirely or upload their own logo. See the screenshots below:

The ticket I was assigned aimed to make the feature of adding a custom logo really work, adapting to different logo sizes. All the customization was done directly by clients using a WYSIWYG editor. To me, it looked like a simple task; honestly, I thought we could just ask clients to resize their logos themselves because we wouldn’t be able to handle every possible format. But the dev who had been working on it before me had started talking about state machines and I was like, what?! He was really trying to solve this in the most complex way possible.

When I took over, I realized that we actually had two stacked divs above the CC form: one for our default logo, and another for the custom logo. We toggled their visibility depending on the option selected. The custom logo div used a background image but wasn’t styled correctly. My fix was to make sure the provided image filled the div properly, and to warn the user if the image was too large or small.

I also simplified the whole thing by keeping only one div and removing the extra space that was showing up when using

the default logo (since the custom logo div was just hidden with visibility: hidden but still taking space). That

cleanup was also part of the ticket’s goals.

I wrapped it up in two days, the PO tested it extensively and was really happy that it finally worked and handled all edge cases.

But, as you might guess… things didn’t go so smoothly once it hit production with real client logos.

The Incident: When Production Broke

The Call, the War Room, and Finding the Issue

The feature landed in the sprint deliverable and was deployed to production on a Tuesday around 10:30. I checked production after the deployment and didn’t see any issue. At 12, I went for my usual 2-hour lunch break (yes, in France we often take 2-hour breaks), and when I came back, I saw that our team’s office was closed with a big “Do Not Disturb” sign on the door.

The tech lead pulled me aside and explained: just after I left, we got an urgent call from one of our biggest clients. Their payment page was completely broken. Since this was critical, the company triggered a war room process to handle the incident.

The customer care team had already applied a quick fix for this client to make their page usable again. But my whole team had been waiting for me to return, so I could help figure out what went wrong and what we should do next. They had spent almost two hours discussing possible solutions—rolling back the code was one of the options on the table. But in our company, doing any kind of release or rollback wasn’t trivial: it required approvals from multiple people and took time.

I noticed something interesting during this process: in these big meetings, decision-making sometimes drags on because everyone’s waiting for someone else to give the green light.

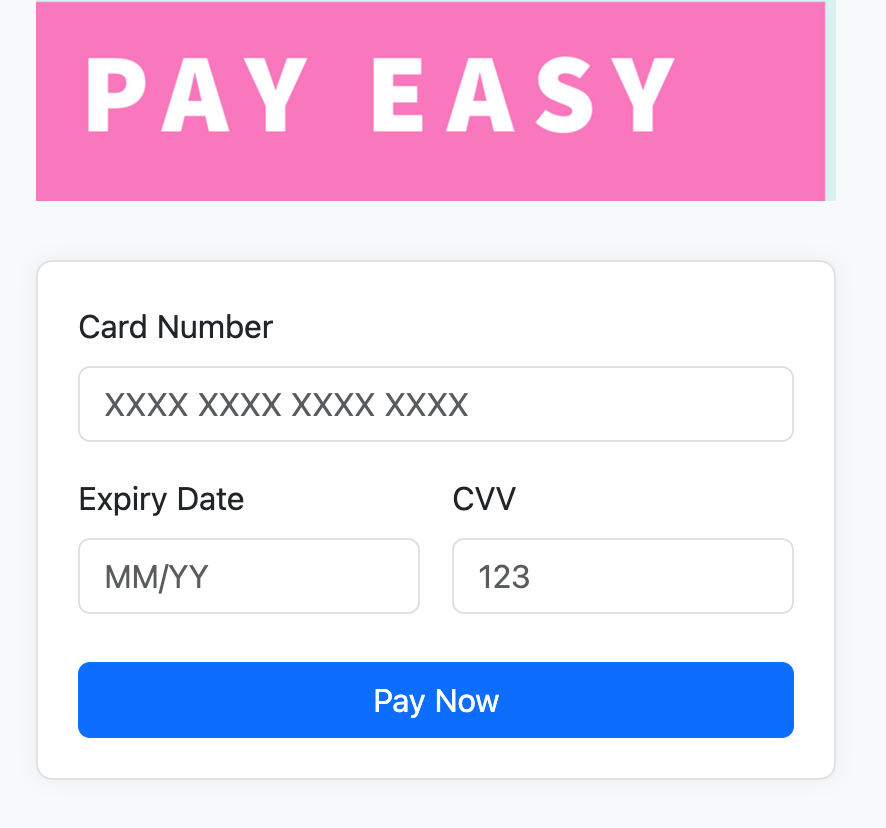

When I looked at the issue, I immediately saw where the problem was coming from. It was related to the extra space I had removed. The client had used the customization tool to move the credit card fields upward to compensate for that space—and when the space disappeared, their form elements overlapped with the header.

You can see an example in the screenshot below.

Damage Control and the Fix

I didn’t have any real experience handling incidents, but I figured the first thing to do was to check the damage. It’s kind of like when your phone falls from your hands—you pick it up and give it a quick dust-off before worrying if it’s really broken.

So naturally, I suggested we start by identifying which clients were actually impacted. The issue only affected clients who had customized their payment page, and since all the customization configurations were stored in the database and converted into CSS at render time, it was easy to extract that information with an SQL query.

We found around 1,000 clients had customized their page, but we could narrow it down further: only the clients using the default header and who had moved the credit card fields upward were impacted. That left us with just 86 clients, and of those, only 3 were major clients processing payments daily.

Our tech lead wrote an update query to adjust their configuration—basically moving the credit card fields back down. Then we manually checked each page to make sure everything was displayed correctly. In total, it took about two hours to fix them all.

I thought that was the end of it—but I was surprised when the tech lead told me to rework the ticket and put the div back. I didn’t really understand why, since everything was working now, but I went along with it. So I restored the div, along with the extra space it originally had, and then we reverted the SQL fixes we had just applied. We manually rechecked everything again to confirm it was back to normal.

What I Learned

This incident taught me a lot. Looking back, it wasn’t just about fixing a bug—it was about understanding how things work in a bigger company and the realities of production systems. Here’s what I took away:

- Solving a problem technically isn’t enough—you have to think about how clients already adapted to existing quirks, even if those quirks shouldn’t have been there in the first place.

- This situation reminded me of that classic joke: “A QA engineer walks into a bar. Orders a beer. Orders 0 beers. Orders 9999999 beers… Everything works fine. Then a real customer walks in and everything explodes.”—because that’s exactly what happened when the feature hit real use cases.

- Incident handling in big companies is more about reducing risk than chasing perfect solutions; sometimes reverting is safer than fixing.

- The way incidents are handled can unintentionally make people afraid to take initiative or deviate from established processes, even if those processes aren’t the best.

- I’m glad this experience didn’t discourage me—my teammates would joke about how I “broke production,” but I never let that stop me from taking initiative or questioning how things were done.

- Over time, I learned how to minimize the risk of creating big incidents while still pushing for improvements and better solutions.